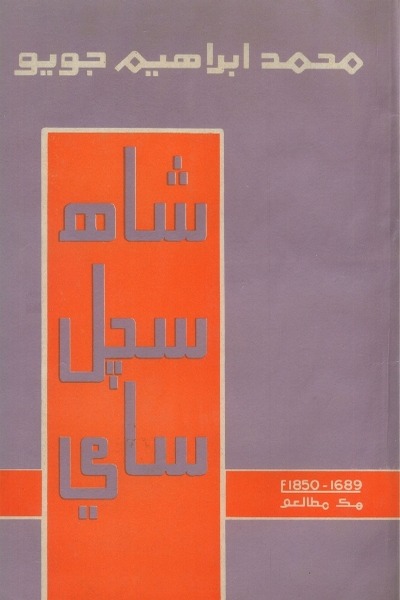

SINDH AND THE MESSAGE OF SHAH

The portrait of Latif (1689-1752) the soul of Sindh, its life-breath, the poet-universal, created by Muhammad Ali, is a unique work of Art. A great amount of study and research, a devoted purpose and reflection, must have gone in the creation of this portrait. It is a serious portrait by a competent artist, done with an artistic simplicity and complexity and artistic integration almost beyond words.

In the portraiture of Latif’s envisioned physiognomy and enduring personality thus, and wirh the study of his character with such a significant insight, the artist has captured an immortal moment in the cultural history of Sindh. The work depicts Latif as a human being pre-occupied with his life and destiny as affected by his physical, social and spiritual environment. Here before us in this portrait sits Latif, the rebel, the individual, and the saint, reflecting upon the fate of human solitude, longing disconsolately yet perennially, for that which could be genuinely good for man, which could even be universal and abiding. A unique individuality of a human event in life’s ceaselessly unravelling story of Sindh and its people has thus been depicted and exemplified by Muhammad Ali, our young and visionary artist, in this matchless portrait of Shah Abdul Latif, the guardian spirit of Sindh and the most unfailing and wakefull friend and guide of its people.

The creation of this portrait of Hazat Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai is therefore, in itself, destined to be an immaculate and unfading mark of pride and honour in the ever developing and self -enriching life and culture of Sindh and of the people of this ever felicitious land of Sindhu -whom the poet himself has idealized in the following ringing words.

نڪا جھل نہ پل، نڪو رائر ڏيھہ ۾،

آڻيو وجھن، آھرين روڙيو رتا گل،

مارو پاڻ امل مليرون مرڪڻو.

This could read in English thus:

No restrictions, no restraints and

No impositions in the Land either,

Freely they bring home red, beautiful flowers

– arm- fuls of them,

Priceless people they, proud of their Land,

And the Land proud of them.

Latif, thus, visualized almost a utopian future, a blissful future, for both his Land and his people,

Indeed, Sindh, during Latif’s times, was awakening to a sense of nationhood and had to struggle for recognition and national self-–expression. Nearly two and a quarter centuries (1520-1736) of foreign rule and tyranny of the savage Mangols- the Arghuns and Tarkhans, and the Mughals (who no doubt were all Muslims), was just ending after a prolonged night of darkness and a suffering, and the incressant flow of blood of her children was coming to a stop, while Sindh attained freedom and unity and her people their independence and sovereignty.

Latif’s “Risalo”, which means his “Message”, represents that quest of Sindh’s freedom and urge for national identity and self-expression. Latif’s was an exhortation to the people of Sindh for self-assertion and self-discovery as a people. Latif’s Risalo is, therefore, more a national classic than a religious or philosophic treatise. It is set forth as a tradition which emerged from the national life of Sindh, rooted in particular in the two of her most glorious periods of history- the Soomras and the Sammas, covering nearly seven centuries (from mid – Ninth Century to 1520 A.D), the great formative periods of her socio-cultural identity.

Latif’s poetry has its literary excellence and sufistic credo beyong measure and description, and it has its artistry and methodicalness too. But, above all, it is a source of strength for the people of Sindh, for it also marks the full extent and maturity of their language as an emblazoning saga of their life and spirit through the ages.

In this Auditorium, while reading a paper on the life and work of Hussamuddin Shah Rashdi earlier in the month, I had said that languages were miracles of nature and some entirely unique phenomena of human history. Emergence of a language ipso-facto meant emergence of a people, a socio-cultural collective, a centre of power and authority. And then, when time came for God too, or for some godly voice, to speak to a people in their language, they, from that point of time onwards simply did not accept living as a second class people or as a nation less-equal among nations. Poland and Ireland were the modern history’s two most remarkable instances of this kind, and if any instance nearer at hand was needed, that two enacted itself recently right in the midst of us and before our very eyes.

Latif, thus, has provided us with a haven, a refuge, and a vitalism, which resurrect peoples and nations to life and save them in times of the wildest of crisis - - the haven being the language and the vitalism being the message. Let us therefore take to the haven and hold fast and pay our heed to the message, the linguistic bond of support and unity, and equality among nations, the identity and peace-ableness, in the interests of justice and common good of all.

Says Latif:

سائين سدائين ڪرين مٿي سنڌ سڪار!

دوست مٺا دلدار، عالم سـڀ آباد ڪرين!

Oh God, let Sindh prosper!

Oh Gracious Friend, let nations prosper!

جان تون ساقي آھيين، تان وٽي وچ م وجھھ،

جود تنھنجو جکرا، آھي ثاني سج،

نينھن پيالو نج، کاس ڏج کھين کي.

So long you are the cup-bearer,

Let the cup not be intercepted and held up,

Your distribution, Oh master of the tavernl!

Is like that of the Sun,

Take the cup of love and give it particularly

To those deprived and weak.

If we, even today, respond to this godly message of “equality among nations” and “avoidance of all interceptions”, ensuring free flow of “the cup of love and sustenance” among all, in the interests of peace, justice and common good, we shall be redeemed and saved- not after death, but even during death – we, that is, not only we in Sindh and others in Pakistan, but all the peoples and nations of the world, threatened by Imprerialisms, national and foreign - -, and the whole of mankind, threatened by what a Sunday Magazine, the Miami Herald’s columnist. Gene Weingarten, has termed “the most terrible technology of all”, the thermo-nuclear technology. Latif’s Risalo, which, again I say, means his “Message”, can indeed work like what the columnist has termed “the lever inside the coffin” to enable us all, if we are not already dead, to open the coffin’s lid and tear apart the shroud and get out. And it also is, again in the columnist’s terms, “the breathing aperture” inside the coffin, so that we would not suffocate before operating the lever or tearing the shroud open to regain our access to free air and our chance and our right to survival.

Let us, therefore, on our part at least, remember always that Sindhi, our mother tongue, the language in which the godly voice of Latif has been heard by us, is the “lever” and his call and exhortation to us for self-assessment and self-realization as a people, is our “breathing aperture”. Let us then unite in our devotion to our land and our language, and finding strength in unity, struggle for equality among nations and for a state of bliss on earth sans interceptions of all kinds, providing love and sustenance in just and equal measure to all. This is the very least we can do as our homage to Latif, our wise teacher and loving friend.

Says he to us:

ستا اٿي جاڳ، ننڊ نہ ڪجي ايتري،

سلطاني سھاڳ، ننڊن ڪندي نہ ملي.

Oh you who are asleep, risei

Sleep so long and entire will not do,

The fruit and felicity of sovereign life

None has enjoyed while sleeping.

Let us then heed Latif’s wise message and hitch our wagon to the star, and sprint along.

The creation of this marvelous portrait of Hazrat Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai by our inspired artist Mohammad Ali, will keep us reminded of our duty to keep awake and maintain the vigil expected of us on the path to touch the stars.

We should be sincerely thankful to Muhammad Ali, our young artist, for creating and putting this yet one more alarm-clock for us on time, here in the Institute of Sindhology, University of Sindh.

May we never forget that Latif, the soul of Sindh. its life breath, the universal poet, and yet our own poet, is sitting here in the gallery of our great national heroes, thinking of us and meditating on our fate, and watching us as to what we are doing about it.

جيئي لطيف!

جيئي لطيف جي سنڌ!

جيئي لطيف جو سنڌي عوام!

Let Latif live!

Let Latif’s Sindh live!

Let Latif’s Sindhi People live!