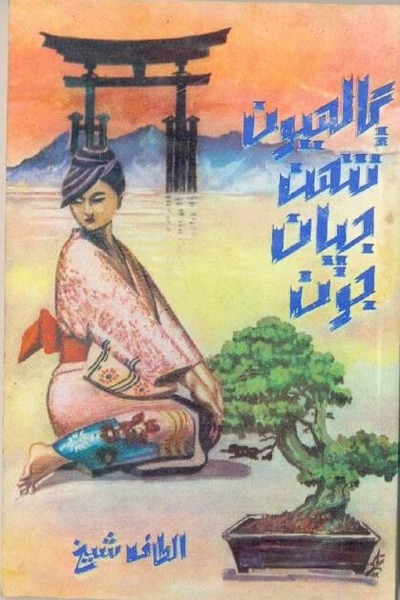

JAPAN & JAPANESE

Yet if what is new in Japan is astonishing, what is old contains even greater wonders and marvels. At some quiet, still, central place in the Japanese psyche, the people of Japan hold, without concession, to aesthetics, ideals, and societal bonds unchanged in twenty centuries. More than any other nation of the East, Japan has remained to itself. Japan has confidence that its past is valid in the present.

Japan is a mountainous country consisting of the four main islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Shikoku and Kyushu, and numerous minor islands. The islands of Japan extend for about 1300 miles from north to south and have width of 170 miles at the widest point.

In 1637, after a bloody revolt, the Shimbara uprising, Japan was hermetically sealed off from the outside wrld. It created one of the many Iron Curtains of history, much more savage and effective than Stalin’s was at the height of his paranoia. No Japanese was allowed, under pain of death, to leave the country, and any Japanese who was foolish enough to return from abroad was executed in a rather unpleasant manner. Foreigners were not permitted to enter the country at all; if they did, they were beheaded.

Although geographic isolation has made Japanese very conscious of borrowings from aboard, it has also led them to develop one of the most distinctive to be found in any civilized area of comparable size.

The Japanese are always strongly conscious that they are Japanese and that all other people are foreigners. Isolation has made them painfully aware of their difference from other peoples and has filled them with an entirely irrational sense of superiority.

For Japan’s defeat was as novel as the Atom-bomb. She had never experienced either. It is true that Commodore Perry forced America’s will upon the country but that was no military defeat. All Perry did was to deliver a letter from President Fillmore to Shogun, in the summer of 1853, demanding the opening of trade relations. Before leaving, he made a show of force by sailing up Yedo (Tokyo) Bay in defiance of Japanese government. The Japanese had never seen a steamship before and were duly impressed. Japan benefited from this lesson so effectively that half a century later she was able to inflict a resounding defeat of land and at sea on one of the greatest and most dreadful military powers of the world. In the First World War she was not one of the major belligerents but with her navy she was an exceedingly useful ally.

In any case, the beginning of the Second World War confirmed the legend of Japanese invincibility. Having nearly knocked out the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbour, Japan advanced and occupied South East Asia including the impregnable fortress Singapore; sank two British Ships; invaded New Guinea; bombed Australia; threatened Indian – and all this with a speed that made the German Blitzkrieg look like a boy scout’s war-game.

The Japanese public knew all about the victories; it knew little about the subsequent reverses. When defeat came it seemed even more crushing because it was unexpected.

The devastation, horror and inhumanity of the bomb were unspeakable and I am not trying to diminish its effects, neither am I trying to be frivolous when I say that, in the long run, the bomb had certain beneficial effects on the Japanese psyche. It rid them of guilt. It surely tilted the moral balance in their favour. They deserved sympathy not condemnation. Japanese, so ingenious and eager to learn, absorbed the lesson as they saw it: nuclear bombs are not to be copied but avoided as evil. Japan has turned away from aggressive military chauvinism and has embraced a substitute nationalism: economic glory.

Japan has not been a major creative force in world history, at least until recent times. The slender arc of islands gave rise to no classic civilization of its own that could impose its style upon surrounding people. The Japanese achievements has been more confined. It has been the particular destiny of the Japanese that they lived within two contrasting great traditions (Chinese and Westerns), and it has been through their genius that, while accommodating to both, they have achived some stature and distinction in each. From the sixth century until the middle of the nineteenth century, Japan has immersed in the Chinese zone of civilization: after 1854, hurried modernization assimilated Japan within the expanding frontiers of western influence. In each of these contexts, Japan played an important, thought not commanding, role. In East Asia, from atleast the eighth century, Japan ranked high among the countries surrounding China in its political and cultural achievements. The Japanese absorbed many elements of Chinese civilization- the written language, techniques of government, styles of architecture and art, and systems of philosophy had learned, and thus retained a cultural style of their own. A thousand years later Japan led the way among East Asian countries in adjusting to western civilization. But again as any visitor to Japan must agree, the resulting cultural fusion is something that bears the distinct stamp of Japan’s own historical heritage.

Japan is remarkable country and the Japanese an extra ordinary people. Their life styles are fascinating blend of ancient traditions with the most advanced technologies and modes of contemporary urban life. Their land is small but varied and beautiful. Man and nature have conspired to make it a visual wonderland. On the one hand there are rugged mountains, majestic coastlines and pleasing patterns of a garden like agriculture, the stately monuments of a rich cultural past and the dynamic sprawl of a vigorous industrial society.

It’s a delightfully mixed up country- where many things seem to operate in reverse. Before going to Japan I was warned by many people who knew the country well that one should never ask a straight question in Japan; if one does, one never gets a straight answer. Personal questions are even more out than in England. One cannot form friendships, and one cannot even get on reasonably close terms with a Japanese, and one cannot – most definitely not – joke with them. Imagine, then, my disappointment when I kept finding interesting, responsive people every where I went: open hearted and broad minded men and women, ready to discuss my public or private problems - so long as they felt that my questions were promoted by real interest and not by idle or offensive curiosity. And quite a few of them were amusing and witty.

This seems to point to the fact that the Japanese are human beings like the rest of us, but they want to be different. They are determined to be puzzling, quaint and unfathomable; they insist on being more Japanese than most of us.

Life in Japan seems to be full of opposites: one washes before getting into the bath tub. Department store `bargain basements` are on the top floor. Papers are stapled in the upper right hand corner, romance and inspiration are associated not with sunsets but with the rising sun. On St’ Valentine’s day, women give the gifts. Stand up comedians don’t stand for their monologues, they kneel. Wine is taken warm while the fish (sashimi) is taken raw without cooking. Towels are used for wetting not drying. The word ‘san’ is used for ‘Mr’ as well as for ‘Miss’ and ‘Mrs’. A foot-note is written on the top not in the bottom.

The Japanese have the habit of absolute and almost religious courtesy in their social relations. The habit of courtesy is embedded in the very language they speak. And there are no foul curse words in the Japanese language. A quarter of an hour in Japan will convince you that you are among exquisitely well mannered people. Among the people of the Far East, the Japanese are practically unique in their fondness for taking baths. Their passion for cleanliness is, in fact stronger than that of almost any other race in the world.

The Japanese cherish custom. It give them a sense of security and identity and history. True, some old rituals are dying. Hospitals no longer give a new mother a small paulowina-wood box containing the umbilical cord of her baby, to be kept as the `uncontrovertible bond between mother and child`. But the Japanese remain the heirs and defenders of a great body of other customs. The Japanese eat and drive and dress and wed and give and shop in thoroughly Japanese ways.

Japanese are competitive people and they want to shine; they want to be first in every field; they want admiration. The Japanese want to beat Americans at base baru (base ball). They want to produce better keki (cakes) & cars, better photo-graphic cameras & teribee (televisions) better transistor radios and VCRs, they produce more flavours of ice-creams than the United States, the nation hitherto generally revered as the greatest ice cream nation on earth.

Japan is still, and always will be, an exotic country. Japan has, and always will have, sublime Fuji-yama, exquisite calligraphy, the beautiful geishas, gorgeous cherry blosssoms, moon viewings, chop sticks, gargantuan Sumo wrestlers, begging monks and polished cedar. Japan is the country of Koinobori (Fish shaped flags flown on boy’s day), Karakasa (oiled paper umbrellas), Sana kobachi (cermic cups and bowls) Sento (public baths), Sake (rice wine), Take (bamboo), Ikebana (flower arrangement), Harakiri (suicide), Origami (folded paper toys) and Soroban (wooden calculator).

Altaf Shaikh

Osaka Port-Japan.